How one veteran’s battle with guilt inspired an initiative

Many of us know a friend, close family member, relative, classmate or person within our lives that has served their country, in some instances sacrificing their lives fighting for this nation.

Oftentimes we overlook just how much that time may have affected the ones we love most, to the point in some cases that the oversight is our last memory of those we cherished.

“The Long Walk Home” seeks to turn that potentially fatal oversight into lifesaving overcoming.

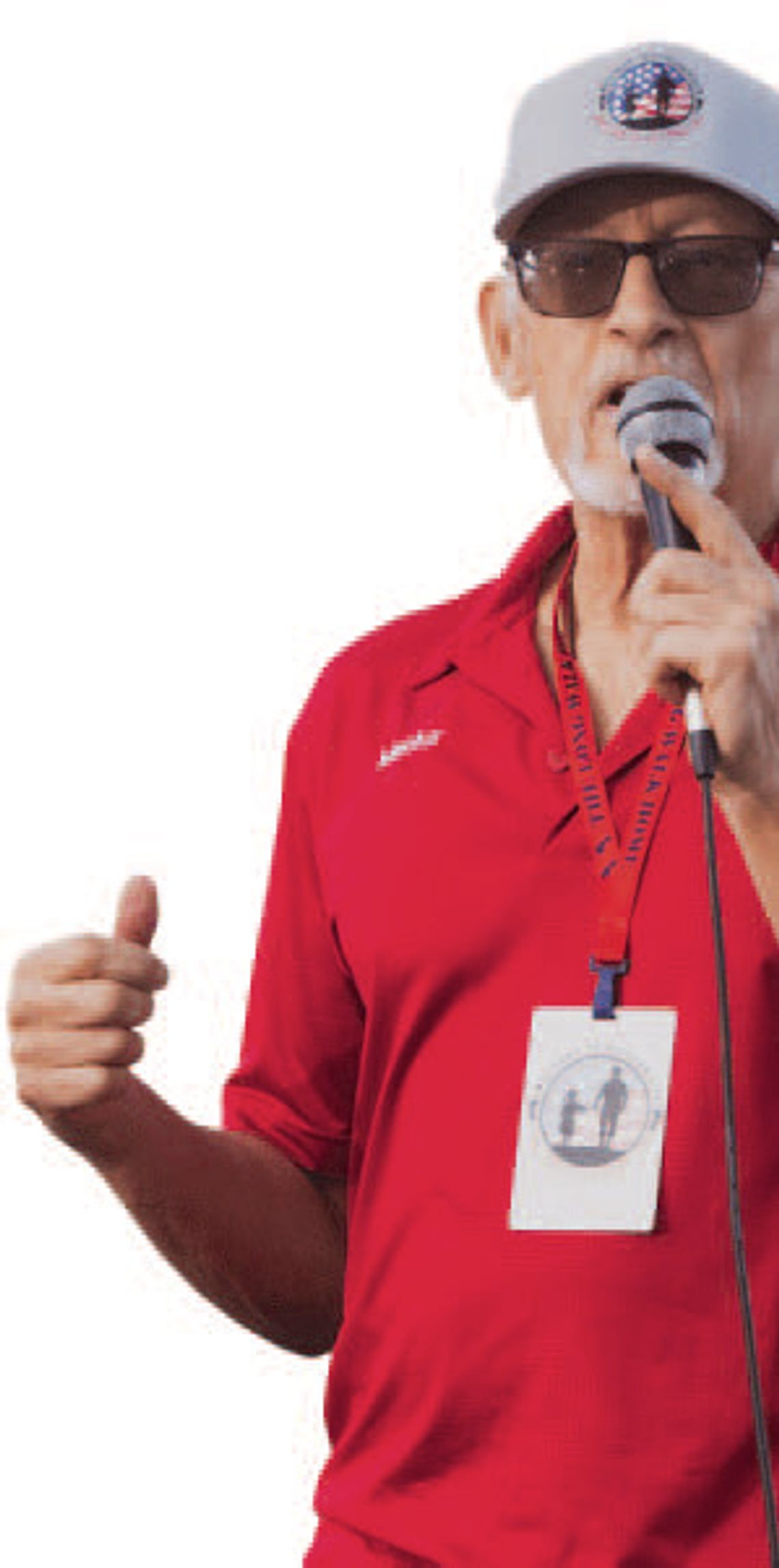

A veteran-led nonprofit organization founded in 2006 by Ron Zaleski, the initiative raises awareness through a nationwide trek carrying a sandwich sign, all by foot, on mental health and suicide rates amongst veterans and active-duty officers, with 22 men and women on average, taking their lives every single day.

Zaleski and another member of the organization, 15-year Coast Guard veteran Omar Rose, made their way through Colorado County Jan. 16 through Jan. 18, having begun their journey in Key West, Florida walking 12 miles every day switching back and forth between themselves until they reach their destination of San Diego, California.

Zaleski’s own battle with mental health and suicidal thoughts began as a teenager between the ages of 17 and 19, enlisting in the United States Marine Corps, having served in the Merchant Marines during the Vietnam Era from 1970 to 1972.

Growing up as a self-described “good catholic,” he was shocked to learn the “true nature of war” on a military ship delivering weapons to Middle Eastern nations after signing a peace treaty with Israel.

His first thought of suicide drifted through his head caught between a “rock and a hard spot” feeling that he would either go to hell for being complicit in war or taking his own life. Zaleski opted to enter the draft lottery and won following this encounter, but realized deep down he was “afraid and wanted to live” and did not have the “courage to not shoot another man.”

By his own self-described stroke of luck, Zaleski’s orders were changed, and he didn’t board the coastal ship five of his friends did to make the trip to go fight abroad. A month before he was set to complete his duties, he met one of the five, limping, who told Zaleski that all of them had been shot, leaving two dead.

“I felt anger, all those emotions at once,” said Zaleski. “Did I do the right thing? Was I a coward? Could I have saved him? When I got out, I didn’t wear shoes because I figured it would be my memorial for my friends that died and suffered, but it wasn’t. It was just an act of defiance because people would say to me, “how come you don’t wear shoes?” I’d say, “I don’t feel like it, you got a problem with that?” Thus began Zaleski’s journey with what he felt at the time was atonement, going barefoot in 1972. He would deflect as to why he would do so, citing his own inner anger as a source of lashing out against those questioning his decision.

It wasn’t until 33 years later that Zaleski answered honestly about why he did so, to a child he was teaching as part of his job as a swim instructor. That was Zaleski’s turning point and the birth of what would soon be “The Long Walk Home.”

“One day I’m taking the kids to the pool edge to swim and this kid tugs at my bathing suit asking, “why don’t you wear shoes,” said Zaleski. “That was the first person I told why, it was out of left field, he didn’t say it with malice or judgement, only curiosity. It was like God hit me with a two by four and said, “what are you doing?” That’s when I realized I had a problem and I can’t live like this anymore. That was a huge turning point.” After experiencing another bout with suicidal thoughts following his divorce, in 2006, Zaleski dropped everything, including selling his scuba business and founded the Long Walk Home. That same year, he set out to walk barefoot across the Appalachian Trail, traversing 2,200 miles of woods and wildlife, “learning self-forgiveness, empathy and finding a purpose greater than himself,” all barefooted.

Initially, Zaleski admitted he completed the journey for himself, in search of the inner peace he had been seeking for so long. After finding that peace, he set his sights on a new mission.

In 2010, he upped the stakes and walked barefoot from Concord, Massachusetts to Santa Monica, California. He traversed over 3,400 miles without shoes, carrying a sign that read “18 Vets a Day Commit Suicide!” and a petition for military personnel to receive mandatory counseling. In 2011, Zaleski brought that same petition, which had at that point accumulated over 20,000 signatures, to Washington D.C.

Along the way, Zaleski encountered veterans just like himself and loved ones of veterans curious to hear his story and eager to share their own. Zaleski says through his journey, he’s saved thousands of lives, crying at one point every day for 10 and a half months.

“Every day, a mother would stop me,” said Zaleski. “Hold me like I was her son, blame herself for his death, and cry and hold me like I was her son. It was brutal. In the beginning, I didn’t cry because I was numb. But after that, I mean, I cry all the time.”

Since then and for over a decade, Zaleski has worked tirelessly to build The Long Walk Home from the ground up. One of the hallmarks of awareness involves a four-hour long program comprised of 10 challenges in four different phases to help veterans navigate life after service.

“78% of the guys that kill themselves do it because of a failed relationship,” said Zaleski. “Their spouses don’t know how to deal with a guy that’s angry. That’s what our program does. It helps them. Our program takes four hours, and it helps you shift your perception and it also helps the family.”

Zaleski hopes that by raising awareness on the topic, family members and loved ones can become more aware of how to help a veteran they may know integrate back into a normal life. He feels that the same effort that is put into their training to learn how to kill should be put into how they live after serving. “What I would really like to see is that they do a boot camp on the tail end of your service,” said Zaleski. “Three weeks to 12 weeks, because they train you for 12 weeks to go kill, so why is it any different on the tail end, to help you come back, because you’re not the same person anymore. You don’t know how to integrate anymore. War is not evil. It’s stupid. We glorify it by calling it evil but look at the destruction. Look at what it does to young men and women. 10 times as many soldiers die after they come home from combat. When you come home, you’re angry at everybody. You ask yourself, “what did I fight for?” I’ve lost my family.”

.jpg)