Eagle Lake Remembers

One Sunday afternoon I was fishing with a long, cane pole on the rice canal bank. A few summer gnats were the only thing between my pole and me, and an unsuspecting catfish.

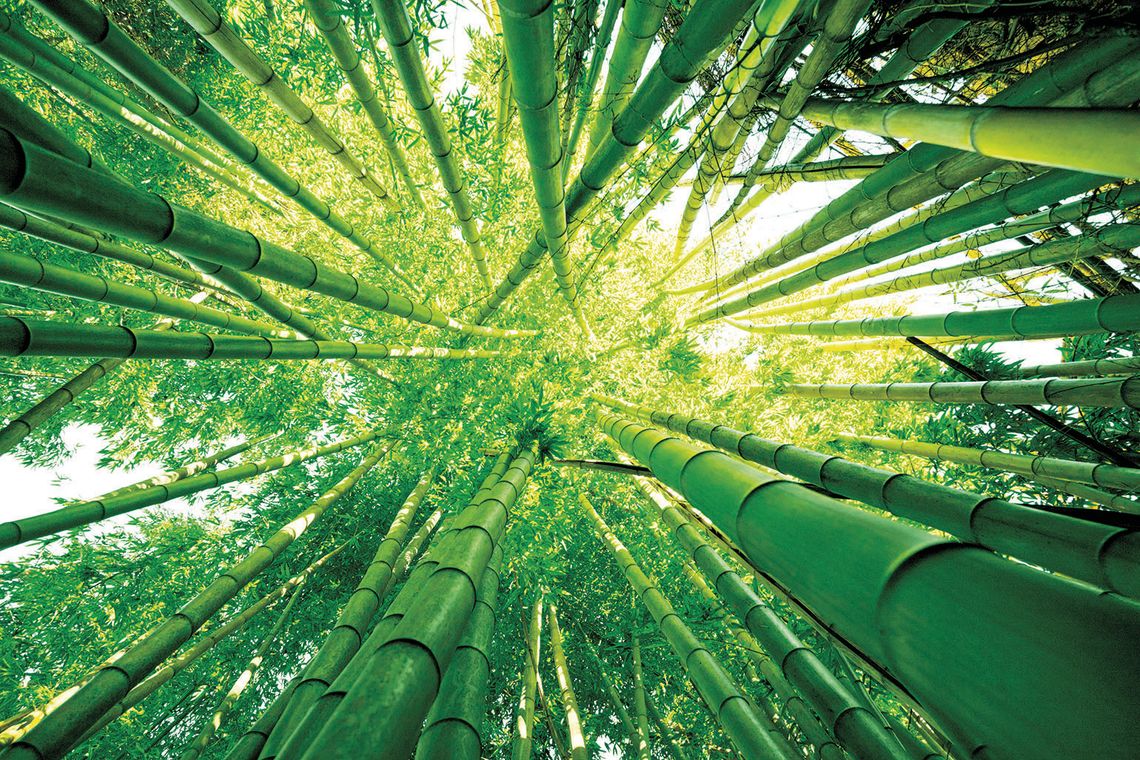

An old-timer fishing nearby was watching my pole as he asked, “did you know that those old bamboo cane poles used to be so thick around here that a man couldn’t find his way?” I looked up with wide imagination. “They would grow mighty near up to 35 feet high and so thick you couldn’t see the light of day from here all the way to the coast,” he said.

I put down my long, bamboo pole to learn about the famous “Old Caney Creek,” which had its beginnings right here in Colorado County near Eagle Lake and Matthews. It was at first called the Canebrake River, and was the channel of the Colorado River over a thousand years ago. The Karankawa Indians believed that the Great Spirit flooded the area, creating two larger rivers, the Brazos for the White man, and the Colorado for the Red man, leaving the “Old Caney” as a creek alongside the Colorado.

While you don’t hear much about “Old Caney” anymore, it and the Bamboo Trail created the rich, fertile, alluvial soil just south of Eagle Lake. Its 155 winding miles to the Gulf of Mexico near Matagorda, between the Colorado and the Brazos Rivers created the great “Sugar Bowl” of Texas.

Caney Creek even today closely follows the path and bends of the Colorado River, from Matthews to the Gulf of Mexico, connecting with the river for several miles around Glen Flora. As the former bed of the Colorado River centuries ago, Caney Creek was among the seasonal hunting and fishing grounds for the Karankawa Indians.

Oddly, a native Texas bamboo (Arundaria) grew up on both sides of “Old Caney” and became so thick and tall that settlers lost their way and traveled around in circles unable to get through the tall cane. The bamboo grew up to 35 feet high and extended 45 miles wide and 75 miles long from the banks of the creek outward from both sides. It was unforgiving to early travelers. They had to cut their ways through it with machetes.

I imagined from my canal bank perch how hard it must have been for families to make their way through these canebrakes through Matagorda, Wharton, and Colorado counties. But there was a good side to the many miles of bamboo cane. Each season for centuries, as it would decay along the Caney Creek banks and outward, the tall bamboo cane residues created some of the richest, most fertile soil in Texas.

Settlers used the bamboo cane for fishing poles, fencing, cattle feed, flooring, matting, hats, roofs, beds, and building. Early settlers in the area began to take out the cane to create passable trails, farms, and fields. They would cut and burn the bamboo cane removing it for the farming of sugar cane and cotton. Both crops were prolific due to the fertile soil and proximity to the creek and the two rivers. The Sugar Bowl lay in the fertile area between the Colorado and the Brazos. Even today there are remains of old plantation homes and sugar mills along the creek bed. Small sugar mills and cotton gins dotted the Caney countryside. The Lakeside Sugar Mill at Eagle Lake was among the largest in the state.

In 1838, after Texas became a Republic, mail routes were established in Texas. The route that was established from Matagorda through Wharton, Eagle Lake, and up to Columbus was called the “Old Caney Run,” meaning mail run. The small town of Caney, named for Caney Creek, and its 1838 post office were established in Matagorda County along the mail route.

The Caney Run was also used as a wagon trail for freighters, large wagons which carried goods and materials for new settlers and for trade. Early freighters were oxcarts pulled by three to six oxen on cart beds up to 15 feet long to carry heavy freight. Later mule-driven wagons carried heavy cargo in caravans of wagons of goods and freight. Caney Run was the early highway for settlers and traders from the port at Matagorda north and westward through Eagle Lake to settle the state. The old trail continued until the railroads came in the early 1900’s.

The “Caney Creek” is still visible. Its water comes and goes along the way, but as it meanders southward towards the Gulf, it picks up steam taking in water from drainage areas nearer the coast, as it flows solidly into the intracoastal canal and the Gulf of Mexico.

Most of us have been through the Caney bottom near Eagle Lake many times. While the bamboo forests no longer exist, we enjoy the benefits of the prolific cotton and corn fields from the rich soil. We can thank the miles and miles of native bamboo along the Caney Run for the gift of fertile soil for our crops.

As I looked down at my old bamboo cane fishing pole, I examined it carefully. I had forgotten about the catfish and the bait. I had just heard a remarkable story. As the old-timer tipped his hat and strode away with his cane pole over his shoulder, I knew that Sunday was about far more than fishing.

It was about thousands of acres of corn, cotton, and sugarcane. It was about the building of the largest sugar refinery in Texas near my seat on the old canal bank. It was about pioneer settlers and their families. It was about Stephen F. Austin bringing his old 300 pioneers to our area of rich farmland. It was about the Canebrake River and later the Caney Creek forming near Matthews and Eagle Lake. It was about the great Texas Bamboo Trail.

I, too, picked up my bamboo fishing pole and headed home. I had no fish to gather, but I had caught one of the most important stories of my young life. I had learned about the “Old Caney Creek,” and the Texas river bamboo.

.jpg)